It’s Everywhere: Sources of E. coli Infection

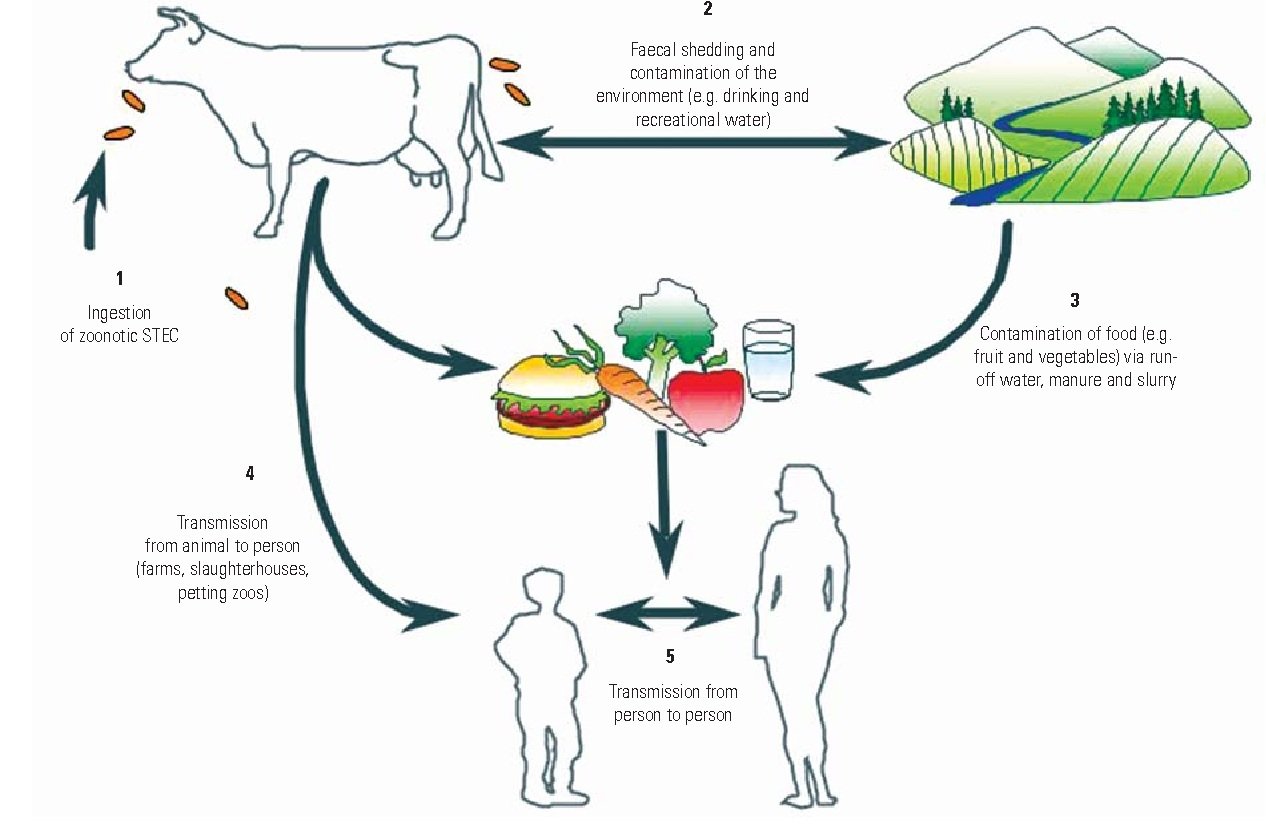

E. coli bacteria can be found everywhere, from your food and drinking water to your swimming pool to your local petting zoo.

Escherichia coli, or E. coli, is a bacterium commonly found in the intestinal tracts of warm-blooded animals, including humans. Although most strains of E. coli are harmless, a handful can cause disease in humans, the most common being E. coli O157. Infection with one of these virulent strains can cause symptoms like diarrhea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and fever, even leading to death in select cases.1

Infection with E. coli occurs most commonly when the bacteria are ingested, meaning contaminated food and beverage products are usually the top suspects. However, E. coli can also spread through contact with the eyes, nose, mouth, and open wounds, making swimming in contaminated water and touching infected animals equally as dangerous.1

Flowchart of E. coli transmission

Food and beverage products

As E. coli bacteria do not survive at temperatures above 70°C, processed foods are typically safe from contamination.1 Instead, raw fruits and vegetables, undercooked meat, and raw or unpasteurized milk products are often implicated in *E. coli *outbreaks.2

Once an outbreak occurs, the contaminated product is recalled from the market. However, it may be weeks or even months before the source of infection is caught, during which time hundreds of people may consume the product and fall ill.3 But how do food and beverage products become contaminated in the first place?

Fruits and vegetables

For fruits and vegetables, E. coli contamination can occur at any point between the farm and the table. Since E. coli naturally lives in the intestines of many animals, the bacteria spreads after contamination with these animals’ feces. If E. coli contamination occurs during plant growth, the bacteria can grow within the plant’s tissues, meaning it cannot be removed by washing or soaking.4 However, if E. coli is merely present on the plant’s surface, post-harvest processing methods are sometimes able to disinfect the produce.

Preharvest contamination

Before harvest, E. coli bacteria can infect crops through contaminated soil, irrigation water, or animal manure. Soil often becomes contaminated during rainfall, as runoff containing fecal particles may flow from farm animals to agricultural fields.5 Since soil is a natural reservoir for many microorganisms due to their abundance of sugars and nutrients, bacteria can survive in soil for long periods of time. E. coli O157:H7, the most common pathogenic strain of E. coli, may survive in soil for up to 25 weeks, putting crops grown in contaminated soil at risk of infection.6

Contaminated irrigation water can also spread E. coli bacteria to crops, particularly leafy vegetables like lettuce and spinach.6 In fact, one of the largest E. coli outbreaks in recent history was linked to a contaminated irrigation canal that indirectly infected over 200 people across 36 US states7 and 5 Canadian provinces.8 The 2018 outbreak was eventually traced back to E. coli O157:H7 found in an irrigation canal in Yuma, Arizona which provided water for romaine lettuce grown on multiple farms.7

Finally, E. coli contamination can occur if crops come into contact with wildlife. Studies have shown that feces from wildlife such as deer9 , feral pigs10 , or even flies11 can directly transfer bacteria to plant leaves or fruits.

Postharvest contamination

After harvest, the produce is sent to processing plants to be washed, soaked, and packaged before they are ready for sale. While washing the produce can remove potential E. coli bacteria from the plant’s surface, this process becomes counterintuitive if the water itself is contaminated. Washing fruits and vegetables with E. coli-contaminated water will cause the bacteria to spread, making the product unsafe to eat.6

Animal Products

While E. coli is a sign of a healthy digestive system, if an animal carries a pathogenic strain like E. coli O157:H7, contaminated products can be dangerous to eat. Cattle are the most common animal source of E. coli, making it essential to cook meat thoroughly and avoid raw or unpasteurized milk products.

Undercooked meat

Cattle shed E. coli through their feces, which may contaminate their hides and living areas. Consequently, equipment used during slaughter and processing may also become contaminated, causing the bacteria to spread to the raw beef. Since E. coli is unavoidable when dealing with live cattle, intensive processing methods are enforced to prevent contamination, such as high-pressure hot water rinses to kill bacteria from cattle hides and equipment. However, as with any procedure, these methods are imperfect, and E. coli contamination sometimes slips through the cracks.12

Whole cuts of meat, such as steaks, will typically only contain E. coli on their surface, making it easier for the bacteria to be killed off during cooking. On the other hand, when the meat is ground or tenderized, the bacteria is spread throughout the product, making it more likely to cause illness if it is not cooked thoroughly.13 As a result, millions of pounds of ground beef are recalled each year.14

Raw/unpasteurized milk

Similarly, fecal matter containing E. coli may be present on cow, sheep, or goat udders prior to milking. While thorough cleaning may reduce the risk of contamination, pasteurization is the most effective method as it involves heating raw milk to a high enough temperature to kill pathogens like E. coli.15 In some regions, including certain US states16 and Canada17 , it is illegal to sell or distribute unpasteurized milk.

Water

Drinking water

E. coli bacteria may infiltrate drinking water after fecal contamination from human or animal sources through sewer overflows or inadequate water treatment. Sanitary sewer overflows are unplanned releases of wastewater before the water can be processed through a treatment plant. If the sewage (which likely contains pathogens like E. coli) contaminates municipal drinking water sources, individuals can become infected after ingesting the water.18 Similarly, runoff agricultural or stormwater may pollute rivers, lakes, reservoirs, or groundwater used for drinking.19 If not appropriately treated, pathogens such as E. coli may contaminate the water that ends up in household taps, potentially causing illness for those individuals.

Beaches and swimming pools

Untreated wastewater and agricultural runoff may also pollute bodies of water such as lakes, rivers, and streams. Additionally, if improperly maintained (including low chlorine/bromine or pH levels), E. coli from human or animal fecal matter can spread in swimming pools.20 If swimming areas like beaches and pools become contaminated with E. coli, swimmers are at risk of infection. While E. coli is not spread through skin contact, accidentally swallowing or exposing the eyes or open wounds to contaminated water can cause illness.21

Petting zoos

Finally, E. coli infection can occur after exposure to animals or their environments, a prime example being petting zoos. Animals such as cows, goats, sheep, and donkeys can carry E. coli O157:H7 and shed the pathogens through their feces. Fecal contamination can then easily spread to the animal’s skin, fur, and living area. Even worse, since E. coli is a normal gut bacteria, these animals can carry pathogenic strains of E. coli while appearing completely healthy and clean.22

Although E. coli cannot penetrate the skin, meaning that simply touching an animal isn’t enough for the bacteria to spread, the eyes, nose, and mouth can all transmit bacteria. For young children, who are prone to touching everything and putting things in their mouths, the risk of infection is clear.23

Preventing E. coli infection

- Practice proper hygiene

- Wash hands after using the washroom and changing diapers

- Wash hands before and after preparing or eating food

- Wash hands after contact with animals and their environments

- Cook meats thoroughly

- Use a food thermometer to ensure the meat has reached an internal temperature of at least 70˚C

- Wash raw fruits and vegetables under running water

- Prevent cross-contamination

- Wash hands, counters, cutting boards, and utensils after contact with raw meat

- Avoid raw or unpasteurized milk and dairy products

- Don't swallow water when swimming

- Be careful in lakes, ponds, streams, and swimming pools 24

About Kraken Sense

Kraken Sense develops all-in-one pathogen detection solutions to accelerate time to results by replacing lab testing with a single field-deployable device. Our proprietary device, the KRAKEN, has the ability to detect bacteria and viruses down to 1 copy/mL. It has already been applied for epidemiology detection in wastewater and microbial contamination testing in food processing, among many other applications. Our team of highly-skilled Microbiologists and Engineers tailor the system to fit individual project needs. To stay updated with our latest articles and product launches, follow us on LinkedIn, Twitter, and Instagram, or sign up for our email newsletter. Discover the potential of continuous, autonomous pathogen testing by speaking to our team.

Sources

- https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/e-coli

- https://www.cdc.gov/foodsafety/foods-linked-illness.html

- https://www.cdc.gov/foodsafety/outbreaks/investigating-outbreaks/reporting-timeline.html

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC126537/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5203627/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6899298/

- https://www.cdc.gov/ecoli/2018/o157h7-04-18/index.html

- https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/public-health-notices/2018/public-health-notice-outbreak-e-coli-infections-linked-romaine-lettuce.html

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23876397/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2876768/

- https://sfamjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02297.x

- https://www.beefresearch.ca/topics/e-coli/

- https://www.healthlinkbc.ca/healthlinkbc-files/e-coli-infection

- https://www.fsis.usda.gov/recalls?keywords=ground+beef

- https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1471-0307.2009.00504.x

- https://www.ncsl.org/research/agriculture-and-rural-development/raw-milk-2012.aspx

- https://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/public/programs/publichealth/foodsafety/milk_facts.aspx

- https://www.owp.csus.edu/research/wastewater/papers/SSO-Lit-Review.pdf

- https://www.cdc.gov/healthywater/drinking/public/water_sources.html

- https://www.cdc.gov/healthywater/swimming/swimmers/rwi.html

- https://www.epa.gov/beaches/learn-what-affects-human-health-beach

- https://www.cdc.gov/healthypets/diseases/ecoli.html

- https://www.webmd.com/baby/features/kids-petting-zoos

- https://www.cdc.gov/ecoli/ecoli-prevention.html